Here’s two things I believe:

1) Schools should teach that Conservatism, particularly in its post-1970s New Right manifestation, is an appalling sociopathic con-trick designed to enrich a few at the expense of the many.

2) Every child in school should play Rugby League, because it builds character, is a lot of fun, and might eventually provide us with enough of a player base to beat the bloody Australians.

My economics teacher (God bless you, Mr Lingard) taught me the first principle, and I played lots of rugby league at school, which explains the second. Then I got loads of O-levels and A-levels, and I went to Oxford! This was despite going to the sort of school where my nickname was “Gaylord” because I occasionally completed my homework, some kids burned down the science block (not accidentally), two-thirds of the students weren’t even entered for O-Levels, more girls had babies at 18 than went to university, and my form group had three lads in it who missed days not through truanting – well, that as well – but because they had spells in corrective institutions.

So, I demand that every school, everywhere, immediately implements these two policies.

No, you say? But this is what I believe! This is what I want! It worked for me, damnit!

Still no, you say? But look at my school! It was hard. I had to do it tough (cue rap music, scenes of urban decay, silhouettes of sad-looking children), and so I’m an expert in such things. You namby-pamby liberal elite, with your admiration for conservative ideologues and your history of playing 15-a-side posh-boys’ rugby, can’t possibly understand what the kidz need. Shut up. Everyone do what I say now.

How dare you say “No” again! Look at me: I’m PASSIONATE. I’m SHOUTING my passion. I CARE. More than you. More than any of you. I have seen the LIGHT, and only MY WAY works. If you don’t adopt it, you are FAILING the children. I’m STILL SHOUTING. About my PASSION. RARRRRR!

Why do you still oppose what is obviously the right way? It must be because you are in a sect. Yes, that’s it! You’re a sect. You take your radical elitist lefty-liberalism and use it to harm children. You’re part of a secret society dedicated to deliberately preventing children from achieving their potential. You… you… you….”PROG”.

Now, the above is, of course, silly. Only a fool assumes from their own personal experience that everyone else would turn out identically if only they had the same circumstances. Indeed, the root cause of a very large proportion of terrible education policies is the very human, but very blinkered, inability of even highly-educated, highly-placed people to appreciate that their experience, their values, their priorities, are not universal. People are not uniform. This causes great distress to some, who would prefer it if we were all uniform (do I need to mention the words Brexit and Trump here, or is that too obvious?), while it’s a cause for celebration for others, who welcome the wonderful diversity, unpredictability and, yes, occasional stupidity, of humanity.

I’m very much on the liberal end of the spectrum. I’m comfortable with difference. I’m tolerant of behaviours I don’t like, rather than just indifferent to behaviours I don’t care about (so many people confuse tolerance with indifference, but that’s another blog). I do not seek to impose my preferences on others, and long-suffering readers of this blog will note that I have never once blogged that “this worked for me, so everyone else should do it”. I accept the need for compromise. I am, in other words, appalled by the authoritarian movements currently in vogue which seek to impose their worldview on all of us. And education policy is not immune to this upsurge of intolerant authoritarianism. It is a movement I believe we have to meet head on and fight, in our country, in our communities, and in our schools. This one’s about our schools.

I am different from other people, from my neighbours, from you. As a parent, as a teacher, and as a child.

As a parent, my values are not necessarily the same as your values. For example, I know some parents (or those who claim to speak for parents) argue that top of their list of priorities from a school is exam results. Perhaps they believe – erroneously in my view – that schools determine exam results, rather than being a relatively minor influence. But that’s a different point. Their claim is that everything which happens in a school is justified by exam results. If that means a draconian approach to the clothes the students wear, the size of their rulers, or the way they walk the corridors, then so be it.

I disagree.

I would rather my children were not taught mindless obedience at school. I want them to understand the difference between the necessary surrender of one’s agency for the benefit of others (not shouting in class to disturb others’ learning), and the pointless control over issues which have no impact on others (how you walk between lessons is nobody’s business but your own as long as you’re not late and you don’t kick anyone on the way). I want them to question authority, not blindly obey it. I am appalled by collective chanting of slogans, which I associate with horrible dictatorships. If I had to choose between a child who had a happy time at school and made friends, and one who did not, but got a higher grade (yes, I know it needn’t be a choice, but my children would not be happy under the sort of control-freakery practised in some extreme cases), I would, without reservation, choose happiness and friends.

In short, if a sociologist asked me their classic sorting question of whether I would prefer my child, at the end of schooling, to be considerate/curious/self-reliant or respectful/obedient/well-mannered, I’d fall in the first camp without a second thought. I’m not alone. I don’t care much if someone considers these to be liberal values, or middle-class values, or even “elite” values (and has anyone else noted the weirdness of the same people demanding that the only purpose of school is to provide the same exam grades and knowledge as the “elite”, simultaneously sneering at “elite” values? No? Just me, then). They’re my values. They’re my family’s values. They are, overwhelmingly, my friends’ values. They may not be your values, but you need to respect my right to hold them.

Yet respecting difference doesn’t come naturally to authoritarians, with their cast-iron certainties and self-righteousness. I read something only last night where someone wrote that all children would benefit from much harsher discipline of the sort promoted by authoritarians. That sort of statement sends a chill through my bones. Maybe she was talking about her own kids because she thinks she’s failed as a parent and they’re unruly and badly behaved. I doubt it. She was talking about my kids. And yours. She wants to impose her idea of unquestioning obedience on our children, starting from the premise that they are inadequate without it. It was the voice of resurgent authoritarianism, and it frightens me. It should frighten all of us.

I feel nothing but contempt for the sort of school or teacher who say “my way or the highway” to their local community, whether that be over behaviour policies, uniform, or academic achievement (so, yes, I hate grammar schools). You are there to serve your community. Not a part of the community you happen to like and which agrees with you. Not the easy bits of your community. Not just those who vote one way or the other. All of it. Your community is not there to serve you. That means that you must take account of, and do your best to reflect the fact that not all parents are obsessed with grades to the exclusion of all else. Not all parents want their children to be treated like prisoners in a North Korean re-education gulag. Not all parents are comfortable with an obsession over how their daughters, in particular, should dress. Not all parents are supportive or engaged. Not all parents can afford the expensive uniform and prescribed equipment. Schools who refuse to take account of such parents and their children are not serving their communities. They’re serving themselves.

In areas where there are numerous schools for parents to choose from, then this self-serving selection, whether explicit or implicit, can be sustained in the way that parasites can be sustained by larger organisms – living off the system, often at the expense of requiring other schools to take more difficult cases. It’s unpleasant, but few parasites kill their hosts. But in areas where there is little or no effective choice, because the local school is the local school, then adopting extremist positions is a denial of the rights of parents to an education which isn’t either abhorrent to their values or inappropriate for their child.

If my local school – the only one in my town – announced it was emulating Summerhill, abolishing timetables, lessons, discipline of any kind, then I would be appalled, because I don’t want that extreme environment for my children. So would the same people who currently act as cheerleaders for the draconian authoritarianism which is on the rise in our schools. Yet if that same local school adopted total miserabilist control-freakery, my rights as a parent would be equally denied, while those same authoritarians would simply sneer contemptuously at the denial of my right, and my children’s right, to a local state school which does not adopt extremist positions.

A state education system has to cater for all parents, and their different values. It cannot simply say “these are the only values schools will respect (which happen to be mine)”.

As a teacher, my methods are not necessarily your methods. Over eleven years, I learned many things. I learned how to control classes. I learned how best to communicate the information I wished to communicate. I learned how to motivate children to want to be there, do that, achieve this. I also learned, and this was by far the clearest lesson, that there was no “right” way. At the very heart of my professionalism was the understanding that children are not uniform, and they did not all respond in the same way to the same approaches.

Obviously, class teaching places limits on just how individual one’s approach can be – there are only so many minutes available per child. But it seems to me to be crashingly obvious that one doesn’t teach a low attaining Year 7 class in the same way one would teach a high attaining Y13 class. Moreover, when teaching a particularly dry topic, I’d do it differently than when I was teaching a topic I knew students would find intrinsically interesting. I learned to read the moods of students and classes so that I could vary my approach to best achieve my ends. To me, that is why teaching is a profession. There is judgement involved. It is a job in which humanity, in all its infuriatingly adolescent variety, is absolutely central.

I also learned that I was part of that human mix just as much as the children were. I have a character, as they do. I am more comfortable with some approaches than I am with others, as they were. There is no doubt that, for many of my students, what I did in that classroom, and the way I did it, worked for them. I’ve got the testimonials to prove it. But they would also talk to me warmly about other teachers, who took very different approaches, no less effectively. The school had some of the sort of strict, unsmiling teachers who scared the hell out of the kids. It had stereotypical hippy art teachers who were intensely relaxed about informality. There were classroom jokers, performers, didacticists and emoters. And most of us could, and did, do a bit of each as required. But different default styles definitely existed.

I was able to do strict and scary with some stroppy Year 9 classes very effectively. But I couldn’t have done it all the time – I don’t enjoy that approach at all, as it made me, and them, miserable. I could do group work for lessons where I could see the value, but I wasn’t as comfortable with that as I was with the teacher-at-the-front model, which accounted for far more of my time. I could do serious emoting on particular topics, but I much preferred sarcasm and humour. That was me. I became an effective teacher by learning what I did well and not so well, and adjusting accordingly. But I never once believed that what worked for me should automatically be applied by the teacher next door.

I absolutely understand why some teachers hate what they see as a requirement to use groupwork, if they are the sort of teachers who feel most comfortable with a more didactic style. As a wise old AHT said to me while I cried into my pint as an NQT – “You can only teach as yourself. You can’t teach as someone else”. What I do not understand, however, is how some of those same voices who demanded the freedom to teach as they wanted, are now quite vociferous in criticising those who teach differently. As Cromwell put it in exasperation:

“Is there not yet upon the spirits of men a strange itching? Nothing will satisfy them unless they can press their finger upon their brethren’s consciences, to pinch them there……! Had not they themselves laboured, but lately, under the weight of persecution? And was it fit for them to sit heavy upon others? Is it ingenuous to ask liberty, and not to give it? …. . What greater hypocrisy than for those who were oppressed … to become the greatest oppressors themselves, so soon as their yoke was removed?”

This is, on edutwitter, often characterised as a progressive – traditionalist split, as there is a loud group of self-identifying “traditionalists” who criticise what they see as “progressive” teachers and methods which, they argue, are to blame for low educational standards. As many have written, this is a false dichotomy, and much of the characterisation of “progressives” is the erection of a series of straw men. The argument is not really between “progressives” and “traditionalists” at all. The argument is between liberals and authoritarians. I taught in what might be described as a very “traditionalist” style, yet I am quite comfortable with the notion that there are other teachers and classes for whom a different style works well. I can only truly know what works for me, with my students, because of the central importance of those human relationships. I find the arrogance of those who claim that what works for them is thus the only method which should be used by all, to be breathtaking. And wrong.

A state education system has to cater for all teachers, and their different natures. It cannot simply say “these are the only methods which can be used (which happen to be mine)”.

As a child, I was bored stupid in most of my lessons. I was very able, easily mastered most concepts, and found hour-long silences and teacher lectures dreadfully dull. My most common misdemeanour at school wasn’t disrupting others, it was nodding off in lessons. I loathed assemblies and other forms of forced collective activity. I responded best to those teachers who were relaxed, informal, even eccentric. I hated the occasional class where the teacher had no control and let the students run riot, but I also hated those classes where the teacher demanded silence until every tick of the wall clock’s second-hand felt like an hour. Routine and consistency switched me off. Novelty, independent learning and humour motivated and inspired me.

My youngest child loves routine. She likes everything this week to be the way it was last week. She can get uncomfortable or even upset if things differ too much. She really struggles in a disruptive atmosphere. She’s a poster child for the “There Must Be Consistency” brigade!

State schools need to educate all children. Me and her. The very able, and the not very able. The individualists and the collectivists. The chaotic and the OCD. I had to learn to understand as a child that I needed to curb my preferences in order to allow for those who didn’t find it all as easy as I did. My daughter needs to learn that the world isn’t an ordered place, and part of growing up is coping with difference and the unexpected.

A state education system has to cater for all children, and their different natures. It cannot simply say “these are the only children I will educate (who happen to fit my ideal)”.

A state school with a private ethos should be a private school

A national education service cannot be designed around extreme positions. By its very nature, a system which has to educate all of our humanity, in all its different guises, with all its different values, has to fall back on a principle which is so quintessentially English that it has legal force: that of “reasonableness”. Schools which take extreme authoritarian approaches to controlling every aspect of a child’s school experience are, in my view, as unreasonable as schools such as the hippy chaos of Summerhill, as part of the state education system. Because of their extreme positions on issues of behaviour and control (albeit at different ends of the spectrum), they effectively exclude or oppress those members of the community who do not ascribe to their beliefs about how to treat children. There is a space for them in the private sector, where attendance is purely by parental choice, and not paid for by all taxpayers. But any school which claims to be a state school has a duty to educate all students, of all parents, and that means adopting an approach which is reasonable.

This “reasonableness” is, of course, the position of the overwhelming majority of schools nationally. To hear the tone of the ‘debate’, one might get the idea that wherever these shibboleths of the new authoritarians do not hold sway, chaos ensues. Indeed, one teacher from a particularly evangelical authoritarian school described pupils swearing at teachers in other schools to be “the norm”. This mad assertion denies the facts. Millions of students are educated happily and effectively every year by hundreds of thousands of teachers in tens of thousands of schools. Of course there are incidents in all schools from time to time. But it is simply untrue to say that such incidents are ‘the norm’. A self-serving lie. No different from a hippy Summerhill teacher claiming that it was “the norm” for teachers in all other schools to oppress their pupils or stifle their creativity.

No school has a policy of encouraging or allowing disruption during lessons. No school encourages bad behaviour. All schools seek to avoid such things, and overwhelmingly, through reasonable approaches which take account of the reality of the children of their communities, they succeed. Every day there are examples of the best and worst of humanity in those schools. But it is simply untrue to paint a picture of endemic failure in order to justify one’s own particular stance.

Nor is it honest to portray all non-draconian schools as a homogenous mass. I taught at three secondary schools, attended one, and my children have attended two. Each of those schools was different. They each took decisions about how to function, and the degree of control and direction exerted over the pupils, based around what their pupils needed. But all of them were comprehensives, and all sought to deal with children of widely different abilities, values-systems, and attitudes to school. All also sought to obtain support from, and buy-in from their parents. None of them did everything as I would like them to in my ideal world. But I accept that not everyone agrees with me, or thinks like me, or has my values and priorities, and I recognise that all were reasonable places filled with reasonable people doing their level best to achieve the best outcomes (not just academic) for the children in their care.

Reasonable is not a fixed model of what is “right”. It encompasses a wide range of policies, approaches and pedagogies which are often organically grown from the community of parents, students and staff which that school serves. At the core of this is flexibility, professionalism and moderation.

It is blinkered conceit bordering on cultishness to believe that there is only one rigid method which works best when transparently there are millions of examples of different methodologies “working” every single day. It is no different from me waving my drawerful of letters from grateful ex-students, and then demanding that everyone else employ sarcasm and informality in the classroom, because that’s what I did, and look at their results! It is also deeply insulting to those hundreds of thousands of teachers to portray them as uncaring, inferior or lazy simply because they choose to pursue the interests of the children under their charge in a different way which suits them better.

If you only wish to serve those who share your values, approaches and beliefs, then fine. Set up a private school, and invite fellow-believers to send their children there. If you’re right that this is what most want, you’ll be so overwhelmed with entrants you’ll soon expand and can offer free places to the less affluent parents who subscribe to your particular brand of extremism. This is, after all, what Summerhill’s hippies do. It’s also what extremist religious schools do. I dislike them, but I don’t have to send my children there, and I don’t pay for them. They are not, therefore, denying me and my children anything. But if you have a narrow extreme approach which allows for no differences, and makes it essentially impossible for those with different values to attend their local school, then bugger off out of the state system, because you’re taking our tax money to deny us and our children our rights to a reasonable and inclusive education service.

The split isn’t progressive/traditionalist, it’s liberal/authoritarian

Perhaps authoritarians naturally subscribe to black/white, wrong/right positions. Certainly their twitter feeds, newspaper columns, and favoured politicians all prefer that kind of misrepresentation of the messy complexity of real life. However, just as the alleged split between “prog” and “trad” is a nonsense for the vast majority of teachers, similarly there is no dichotomy in education between a successful, authoritarian, ordered minority and a failing, liberal, chaotic majority. The split appears to me to be more between an extreme authoritarian minority position which does not serve those parents and children with different values, and a reasonable majority position which seeks in a variety of different ways to serve all parents and children.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that those who prefer a more authoritarian teaching style are less tolerant not only of student non-conformity, but of the non-conformity of adult colleagues and institutions. That is the nature of the beast. Any historian can provide chapter and verse on how the desire to control others and persecute difference is a constant urge in humanity. And this is a good time to be the sort of person who demands uniformity and seeks to “take back control” to an earlier, better [imaginary] time. I can well see why those who would “press their finger upon their brethren’s consciences, to pinch them there” might be feeling emboldened right now.

This is a difficult battle for liberals to fight. My instinctive liberal reaction to authoritarian schools, for example, is to shrug and say “well, if it works for the teachers who like that kind of thing, and those parents don’t mind their kids being treated like that, then fine”. And, to be honest, if they were in the private sector, as some sort of negative image of Summerhill, then that would be that. But the authoritarian movement is not in the private sector (indeed, many private schools would never treat their students the way some authoritarian extremists believe we should treat state school students) and quite clearly they are keen to impose their methods everywhere. On me and my colleagues as teachers. On me and my neighbours as parents. And, crucially, on my children as students.

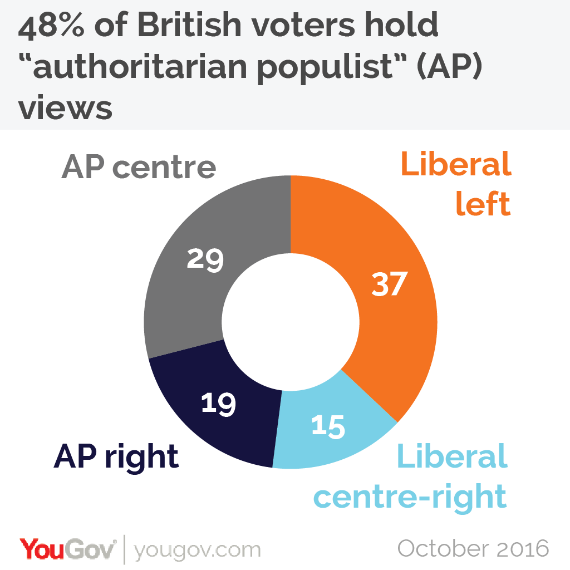

Plenty of commentators have noted recently that there isn’t necessarily any longer a relationship between authoritarian and right, or between liberal and left, in this debate or any others. The dividing line has shifted in 2016. Everywhere in the anglo-saxon world, authoritarianism is on the rise. Everywhere, its characteristics are similar : proclaim certainty, assert “traditional” values, deride difference, dismiss opposition as “elite”, claim to represent “ordinary people”. Many in the new authoritarian movement will genuinely see themselves as of ‘the left’, and argue that what they do is for the benefit of the downtrodden, who have been sold down the river by the liberal values of the middle-class. Of course, every single illiberal demagogue, whether communist or fascist, has made the same claims over the last century. Every one of them justified their removal of people’s rights, and their forcible imposition of their own views, by claiming they were defending the little people, who wanted strong discipline, leadership and traditional values, against a decadent middle-class with alien liberal values. They all claimed that their ends justified their means. They all claimed they had been blessed with a particularly accurate, correct vision of what worked.

If those of us who subscribe to liberal tolerance have learned anything in 2016 it is surely this: we didn’t win the culture war, as we thought we had; liberalism is not safe; tolerance is not universally accepted; individual rights to equality are not respected by all. There are always more authoritarians, of left and right, itching to sit heavy upon us. To put us in boxes. To demand we unquestioningly accept their infallible leadership on the march to a brighter future.

That future is currently in our schools. These new authoritarians might seem to have the wind in their sails at the moment, but it’s time we stopped apologising for understanding the complexities of reality, stopped deferring to the zealots who claim to have all the answers, and started to fight for what we believe in.

I really like extended writing because it’s the only way to develop extended thinking. Thanks for this. The last paragraph contains its own sequel. You’ve carried the fight through this piece without apologising and you’re not alone. I met someone the other day who’s making radical changes to her ITT work, who told me she’d never set foot on twitter, one of a quiet army of people moving things along without fanfare. That’s why it’s good to think and write because once inscribed it’s a resource for us all, blowing a trumpet! Very best wishes. Geoff

LikeLike

Thank you. I recognise that the debate on twitter and in the blogosphere represents a tiny fraction of teachers and an even smaller number of parents. Yet that is not to deny its influence. The institutions with power – Ofsted, DFE, academy companies and suchlike, watch this sphere closely. If the voices opposing the new authoritarianism are too quiet, then those same powers will use the dominance of the authoritarian voices in this arena to claim popular backing for implementing their policies.

We have to be vocal. We have to fight. Or our children will find themselves suffering as a result.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I like this very much. Very much indeed.

Two things.

1. RARGH not RAAAAAAAARRR

2. I found myself debating, last Saturday, on the quasi-religious nature of the ethos/practices at an authoritarian (I imagine!) school – because as a Christian, I find myself creeped out, and as a parent I am very uncomfortable with them – to find the argument that it was alright for me because I am giving these values to my own children in the way I bring them up.

One of the problems with education, as I see it, is that schools have become both the whipping boy and the holder of responsibility for many (if not most) of society’s ills and has taken upon itself the duties of parents.

Now, I’m all for a welfare state, but not, it seems, one that takes on the responsibilities that actually belong to parents. As educators, our mission is that – and the other stuff, the values, come as by-products.

It seems to me that this is a path upon which I am not willing to put my feet – we, as a society, can aid parents to do their job well – but we don’t do that by doing their job for them.

Besides which, if you want to be an evangelist, go work for a church, I reckon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. The quasi-religious flavour of a lot of new authoritarianism in schools in particular, is impossible to miss. There is a real sense of people seeing themselves as “saviours” of the poor benighted children. Some schools even publically rubbish the backgrounds of their pupils and families, in order to claim credit for “saving” them from themselves. I find such things abhorrent.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am extremely uncomfortable with it.

It reminds me of all those adults who say, ‘I hated being forced to pray in assembly when I was at school’ and become virulently anti-church-of-any-kind as a result. Makes me wonder about the young folk at schools like this, and how they will feel when they are adults.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It makes me wonder whether a school with an ethos like this ought to really be a faith school. 🤔

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much to agree with, hence this very long and rambling comment!

“…many private schools would never treat their students the way some authoritarian extremists believe we should treat state school students”. This, this, this.

Find me a brochure for any private school that doesn’t stress how they value each and every student as an individual. How they aim to create confident, articulate and happy people with rounded personalities and how exam results are a by-product of the environment rather than an aim in themselves. There simply isn’t a private school that markets itself on no-excuses, silent transit around the building and complete compliance at all times. It is all about the individual being allowed freedom and experiences.

Another point I often see raised by the authoritarians is that “every child should experience the beauty of a rich academic education” and that those who say differently are guilty of “low expectations”, “ruining life chances” and particularly putting forward solutions for “other people’s children”.

How much exposure do these people actually have to people who didn’t do well at school in their personal lives? There are plenty of them out in the real world living rich, interesting and happy lives.

50% of people leave school without 5 A-C passes and a large subset without any qualifications. All these people have been offered an academic pathway for 11 years but haven’t been able to or wanted to engage with it. Does anyone ever ask them why?

I have and the answer I most often get is “I just didn’t see the point of what I was asked to learn and I was made to feel stupid all the time”. Of course everybody should be a confident reader, writer and be able to do every day mathematics but I do wonder whether we should be telling children they are failures because they can’t write an above average essay on Great Expectations or do algebra. My solution would be a much more basic certificate of competency in literacy and maths accessible to all and developed by government/teachers and employers to be set at a standard agreed by all as good enough to operate as an adult in modern life. Dumbing down? Nope just making education accessible to everybody and giving something everyone could aim at. Once they have this (which they can take at any time during their time at school) they are free to explore the rest of the curriculum without the stifling pressure of everything being judged by exams and “you ruin your life chances if you fail”.

When I encounter academic elitists in real life I like to ask them questions about things I know they’ll know nothing about and see how they react. More often than not the first thing they do is to dismiss the point of the knowledge they don’t have “why would anyone want to know anything about X-factor winners?!?”, if they can’t get a few answers in a row it will turn to anger “this whole quiz is pointless anyway” and if other people are easily answering the questions, and even enjoying it, I often find these people then get quite disruptive and refuse to engage any more with the task. The better educated they are the worse they react I find. I then like to say this is what school is like for 50% of the population and they have to go for their entire childhoods. I first noticed this at university when I found myself getting really annoyed when everyone was playing “7 steps to Kevin Bacon” and I literally couldn’t name a film with him in. I ended up sulking like a sullen year 9 pupil when everyone else was playing for hours and making connections between films I’d never heard of.

People are interested in different things and if my children can’t engage with the academic side of life I’ll do everything I can to make sure they get the most out of the rest of their lives. I want a happy experience at school to be the norm, for my children AND for other people’s children. Too many people now are putting forward the argument that the things they enjoy and value are the only important things in life, and to me that shows a lack of empathy that is at the heart of classic authoritarianism.

LikeLiked by 2 people

God yes. Yes. Seriously. YES. You should blog this.

It drives me absolutely mad that the sole goal of many authoritarians seems to be that everyone in a school should be forced to have their values, so that they can become like them. And if they don’t, well, they didn’t try hard enough. My theory is that because academic ability tends to run in families, and people tend to socialise with people of similar ability, most people never really come across what it is to be someone without the same ability. Oh, they accept the existence of SEN, but they dismiss what it is to be academically less able, or less interested, as an unwise choice which can be rectified with enough drilling.

You hear it when people declare self-righteously that the only goal for working class children should be top grades, top universities and top jobs. Well, not all of us can get top grades, or go to top universities, or get top jobs. So what does that message, given out in a thousand school assemblies every day, say to those students who know they won’t be achieving those things? What do those unempathetic adults think it’s like to be a child who is told daily that the only thing which will give their life value is achieving a number which they know they have no chance of achieving?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think your theory is spot on, most of us live in a bubble.

Another thing I’ve noticed is that the debate is being driven not just by the academically able (which would be expected) but by the very highly able. Almost every one of these dominant authoritarian voices seems to be drawn from people in the top 1-5% of IQ in the population.

It worries me that the debate, and the direction of travel of education in this country, is being driven solely by people who thrived in the system.

What about those of us who merely tolerated school and whose interests didn’t align completely with what was taught?

What about the voices of those who hated school? Are they not allowed any say in reshaping the system? Why didn’t they do well? Could we have offered something they’d have preferred and would have been more useful? A lot of people thrived after school when they found something more hands on to do. The amount of times I read phrases like “why are people seemingly proud they can’t even do basic maths?” on these educationalist blogs when later on you’ll read how they can’t change a lightbulb or cook an egg. It never seems to dawn on them that people have different strengths and that cooking is far more useful than knowing what happens to the proteins in an egg when it is cooked. Just be happy that you live in a time period where your particular skills are valued. You are not a better person for being more academically inclined, and non-academic activities are not a waste of time.

LikeLike

I once gave an assembly at my school which was a reaction to the endless Olympics “Work hard and you win gold” type bollocks. It pointed out the huge support systems behind most successful athletes, going all the way back to their school days. It also looked at the role of circumstance and even blind luck in determining life outcomes. I said that a person’s value was not about whether they were first, or earned millions in top jobs. It was what they contributed to others. They were valuable, good people, even if they worked hard and would never get a C. They could be successful in all sorts of ways which didn’t involve a shallow materialistic measure of “success” which means top grades/universities/jobs.

Children cried. For days afterwards, kids I’d never taught came up to me in the corridors and thanked me, often with tears in their eyes. Parents wrote me letters of thanks. One girl gave me a poem!

These were the kids who aren’t going to get the top grades. They know that, and they are told every single bloody day that this will render their lives failures, and that they deserve those failures because the only thing standing between them and our narrow idea of “success” is their own lack of effort. Someone had then told them it was ok to be them. That they were no less valuable than the kids getting all the As and winning all the races. And they responded with desperate gratitude.

It affected me so deeply that I started to question everything I believed about education. About how even the most well-meaning messages by well-meaning people, rather than inspiring and building up our students, are actually depressing them and tearing them down.

As a postscript, the day after the first delivery of the assembly, I went in to deliver it again to a different year group. I was told by a Deputy that I wasn’t going to be allowed to deliver it, because it contained inappropriate messages for the students.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I found your blog a while back after reading up all the mindset rubbish my daughter’s school was suddenly promoting. All this never give up stuff doesn’t sit well with me. Sometimes it is better to give up and try something else, there are lots of things to try.

I’ve no doubt all of us could improve at lots of things if we didn’t give up and tried and tried and tried. But frankly why should we unless we enjoy it or there is an end result we want or need.

Whenever you read the back stories of these people with the “never give up, always believe in yourself” stuff they’ve generally given up other stuff to do it! They just happen to have found a niche in something where they wanted to do well and therefore applied themselves at it, not the other way around.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tim A – you said above you would like to see a ‘basic certificate of competency’. This was the theory of GCSE when it was first introduced. Sir Keith Joseph intended it to be an exam accessible to all pupils which would show what they knew, understood and do. Achievement would range from the basic (Grade G) to the excellent (Grade A, there was no A*). Most importantly, all grades were passes – the grade received would show level of competence.

That humane attitude has now gone. It’s sneered at as ‘all must have prizes’. But this ignores the fact that the ‘prize’ was graded. Politicians, employers and others (including the shouty saviours of ‘poor’ children) don’t just talk about ‘good’ GCSEs (A*-C), they expect all pupils to get five of them including maths and English or they won’t go on to university and get ‘good’ jobs.

An FoI response I received from the DfE made it clear that anything less than five ‘good’ GCSEs wouldn’t gain access to a ‘decent’ job. This implies the DfE doesn’t think basic employment – work such as catering, cleaning, retailing, basic caring – is a decent job. Yet they are essential. It’s almost as if anyone doing these jobs are a class of untouchables (OK, I know I’m exaggerating but who are politicians to say what jobs are not ‘decent’? The only jobs which aren’t ‘decent’ are ones that exploit workers or involve criminal activity).

https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/figures_supporting_goves_claim_t#incoming-454801

LikeLike

Yes, yes, yes, to this … but I also wonder in what context Cromwell said the words you’ve quoted!

LikeLike

Ah, but Cromwell was an enigma, wasn’t he. Judged by 21st Century standards (well, until 2016), an intolerant tyrant. Judged by the standards of the 17th Century, a hippy democrat.

Genuine, though, in his belief that there should be no attempt to impose uniformity of belief or action on different branches of Protestantism. Obviously, he didn’t extend that tolerance to Catholics….

LikeLike

Great post. I’m not a teacher just a parent who’s currently reading the authoritarian schooling ‘bible’ that was published on Saturday. It was starting to get me convinced, but you’ve swayed me back to being not sure again.

I was thinking the school’s behaviour policy was ok, children benefiting from clear boundaries etc. Like not talking, ever, must mean there is no bullying. Clearly no one can be mean to classmates if they only talk about a set topic at lunch. And it has this amazing system for turning disadvantaged ethnic minority children into middle class british children, just by getting them to read Enid Blyton and learn a big word vocabulary. 🙂 And on top of all that the constant fact-drilling is bound to lead to great GCSE results. I know this because my daughter said all you really do for GCSE is memorize a bunch of facts.

But the bottom line is I’m uncomfortable with the idea of authoritarian schools that are good for ‘those children that need that’ but which are not places I’d want my own children to attend.

But then again, education like this will deliver what our schools are set up to deliver, exam results. It will probably be better for social mobility than most over schools. It aims to create middle class educated types, and those types are valued by our rather shallow society. They earn more money and get more career choice. So if this school gives disadvantaged pupils good grades, big vocabularies, cultural capital, and an ambition to go to Oxford, can we really knock that?

I think it will end up with pupils saying how much the place changed their lives, how much they loved it, how much opportunity it has given them…. (like many ex-grammar kids.) And I don’t think there will be very many pupils saying they hated it either. It really does seem to be a happy school despite the control freakery.

Oh dear, I’m almost back to liking the place again…

Of course the problem with expanding extreme schools of this type is that some parents will be very opposed to the ethos but will find themselves stuck with it for their kids. I know how this feels because I’m in Kent where parents find themselves stuck with secondary moderns when they’d much prefer comprehensives. Actually I’m just imagining this in Kent. What if school ‘choice’ becomes just grammar schools and authoritian-style secondary moderns? It would be schools for the ‘want to learn and can behave’ and schools for the ‘you will learn and you must behave.’ Urgh.

Anyway, here I am still weighing it up. I’m a confused liberal flirting with this authoritarian dark side. Thanks for making me think.

LikeLike

I think the con trick being played by many authoritarian schools is to argue loudly that their draconian methods are the only route to all those outcomes you mentioned. But they’re not. There are more than 4000 secondary schools. Nearly all are comprehensives, taking in a wide range of kids from a wide range of backgrounds. Plenty take in a LOT of kids from disadvantaged backgrounds. Yet these are not chaotic places. They’re places where plenty of kids DO learn big words, ARE happy, and WILL get good exam results. All without having to be controlled as if they’re only a muttered word away from a knife fight. Without being instructed on every last aspect of their existence as if they can’t be trusted to exercise their own agency. And what would we prefer: children who behave well because they choose to do so independently, or children who just do what they’re damn well told under pain of sanction?

I recognise this is a values thing. Some parents like nothing better than seeing their kid told to shut up, follow the rules, be silent, conform. Others don’t. I’m one of the latter.

The problem is, I don’t want to change what their kids do – if they want to be silent, walk in a certain way, exercise no independence, then they are welcome to do it, and are able to do so at every school in the country. I have no desire to impose my preferences for lively, chatty, inquisitive and independent-minded children on them. Whereas the authoritarians aren’t content with that for their own children. They want to force my kids to conform to their ideals as well. That’s the dividing line here – as a liberal, I’m happy for them and their children to practice any behaviour they like as long as it harms nobody else. As an authoritarian, I don’t care if you’re not harming anyone else, I demand your children conform to my preferences anyway.

There’s an element of that in all schools, and no institution catering for 1000’s of kids can fully meet everyone’s preferences. But the existence of differences in values and approaches demands that, where an institution is supposed to serve its whole community, it should practice moderation in what it demands, not extremism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a fantastic read, thank you.

There are a few points that I would like to bring up:

1. You identify that “the root cause of a very large proportion of terrible education policies is the very human, but very blinkered, inability of even highly-educated, highly-placed people to appreciate that their experience, their values, their priorities, are not universal”. We can agree about this, and then say, well what if there are some education policies that are backed up by strong, reasonable theoretical and empirical arguments? Clearly your provocation at the start is a reductio ad absurdum, but perhaps there are propositions you could replace them with that are valid.

2. If one is looking to create a successful school system, then the notion that “perhaps [some] believe … that schools determine exam results, rather than being a relatively minor influence” is a pessimistic one, particularly for those students facing the possibility of getting bad grades.

3. You bring up the idea of ‘straw men’ whilst saying that “not all parents want their children to be treated like prisoners in a North Korean re-education gulag”.

However, let me restate that I do find your argument very interesting, and it is put in a way that I have not heard or thought of before. I’m sure will be thinking about it for some time.

Rufus

LikeLike

Thanks Rufus. Those first two issues are huge areas of debate in and of themselves.

Firstly, a lot of what passes for “evidence” in education is very far from the sort of standard used in scientific circles. Often it amounts to little more than “These people found something I liked in one small and unreplicated study, while I’m ignoring those people who found something contradictory”. Be hugely suspicious of those claiming “evidence shows…” in education, as there really is very little which might pass for unarguable. One of the reasons I always argue for flexibility and classroom discretion is because like an awful lot of experienced teachers, I’ve found that just because this thing works with these kids on this day, it doesn’t necessarily work with those kids on the same day, or the same kids on a different day! Learning, like all matters connected to the brain’s operation, is very opaque. If it weren’t, we’d all know exactly what to do, and everyone would be Stephen Hawking!

On the second point, if you’re interested in reading further on the limited nature of the school effect, I cannot recommend highly enough a blog by Jack Marwood. You could start here : http://icingonthecakeblog.weebly.com/blog/seven-fallacies-about-teaching

It’s a difficult area, because it’s slightly counter-intuitive, but actually it’s one of the few areas where there really is a fairly consistent body of evidence which shows that schools and teachers are simply not the major determinants of pupil outcomes. But we tend to gloss over that, as it doesn’t suit a lot of heroic narratives.

3. On the straw man point, I’m guilty as charged. Exaggeration to both make a point and add humour. I do, however, think of totalitarian regimes when I see identically dressed kids standing up and chanting wholesome phrases. It makes me shiver. But like I said, I’m a liberal!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, I will have a look at that blog!

LikeLike

Without schools and teachers there simply would not be any pupil outcomes at all. There’s differences between schools as well as teachers, and there’s the absolute level (the grand mean, what ever you’d like to call it) of what schools and teachers contribute to pupil outcomes. Quite different phenomena.

If learning wouldn’t be that opaque, we wouldn’t all be Stephen Hawkings. The fact that we can’t introspect our own thinking processes, let alone those of pupils, surely is an interesting one. In a general sense we can hypothesise what is happening there while learning, problem solving, whatever. And research, simulate, test, fMRI that. Look in psychology for ‘cognitive architecture’, such as ACT-R models in the John Anderson research group. Or Stellan Ohlsson’s ‘Deep Learning. How the Mind Overrides Experience’.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing this. Your thoughts about your children in education are exactly what I feel about my children. I am so proud of mine being free thinking, sometimes loud, sometimes quiet, kind individuals (as well as their academic achievements. They’ve done their share of detentions, some they learned to change their behaviour from, and some they learned to despise the system from. It all depends on the reasons they were there.

But more than that, it is the duplicity of systems that profess to be agents of social change by emulating the elite, that is so impossible total seriously.

It is possible to create a system where success is possible without the restriction of liberties and freedoms. The ‘shouty’ sector needs shouting out or their voices will dominate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

sorry for typos!

LikeLike

Don’t apologise. I make plenty myself. Wish there was a tweet editing function. Sometimes I’m just cringing as people retweet something I said which has a typo in!

LikeLike

Another great article. So glad that you haven’t given up on the education debate. See this latest

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2016/12/02/bad-testing-and-distorted-curriculum-in-our-primary-schools/

LikeLike

I would like also like to thank you for such a thought-provoking article, which chimes with my thinking and that of my senior team. The closing down on Twitter of any alternative views to the new orthodoxy is deeply worrying but, as you recognise, the total dismissal of the majority of other state schools that have a different philosophy, a dismissal based on no evidence but prujudice/ignorance of a world beyond Twitter, is deeply disturbing.

Thank you again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] is a response to a post by Disappointed Idealist, entitled The New Authoritarianism. If I have understood the post correctly, it is saying that everyone has different preferences with […]

LikeLike

Wonderful article. But I think the ‘no excuses’, total compliance model, which was developed by US charter school chains like KIPP and brought to England by Wilshaw and ARK, will have a short shelf life. It’s been very effective as a PR gimmick (‘high expectations’, ‘climbing the mountain to university’, etc). As an American blogger points out, it produces ‘a convincing façade of educational success’ behind which the looting can go on undisturbed. But ‘no excuses’ is like a Stage 1 rocket booster that will soon be discarded. Stage 2 is ‘personalised learning’ — i.e. standardised computer-based instruction ‘any time, any place, any pace’ — and the marketing of that model will be different. Less poor-black-kids-go-to-Oxford, more ‘virtual schools’, ‘digital badges’, and workforce development.

LikeLike

I started reading this comment nodding in hopeful agreement. Then finished nodding in hopeless despair.

Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I confess, I lean more towards the “Trad” end of the Twittersphere, and some of what I hear from Michaela sounds actually…good. No IWBs. Teach from the front, Direct Instruction style. No triple marking. Sit down and shut up and do the work. Out at 5. It’s interesting, and a world away from my current school. That said, I’m not sure I could work there. For one thing, I find it very hard to get worked up about top buttons being done up/not done up (not exclusively a Michaela thing that, though). As I confided to a like-minded colleague not so long ago, most of the time I don’t even notice. I find it very difficult to sweat the small stuff for more than a couple of days. Well, hours, actually. The assembly you mention sounds really nice, and something that needs to be said more often. I’d actually love to read it, if it still exists in some form. Sadly, it doesn’t surprise me that it was squashed as being “off message” by a (presumably) power-suit-clad growth-mindset-groupie apparatachik. I mused on similar lines (I think) in https://emc2andallthat.wordpress.com/2014/04/14/what-about-the-wombles/

However, it seems to me that what you identify as a new “Trad” authoritarianism could actually be a “We are the masters now” reaction against the old “Prog” authoritarianism — as your Cromwell quote suggests.

There a lot to think about here. Broadly speaking, I am in favour of freedom — including, most importantly, the freedom to take the consequences. For all of us.

LikeLike

Love this comment.

The standout of the Saturday special from the borough of Brent last week was – in spite of myself – the passionate, impromptu, RAAR/RAAGH bravura. But its impact was so compromised by the ‘If everyone’s against us we must be doing this right!’ (or words to that effect). Setting up Us and Them does no one any good. Oh, and also by the ‘Just Tell Em!’ messaging. Three words sum it up? Really?

LikeLike

[…] Many, probably most, teachers subscribe to a version of Voltaire’s philosophy of “I may not prefer your methods, but I respect your right to use them“. A philosophy underpinned by an acknowledgement of the wisdom of Dylan Wiliam’s oft-quoted “Everything works somewhere. Nothing works everywhere“. Unfortunately, a brief perusal of edutwitter on any given day will suggest that for a subset of teachers, their philosophy may be better phrased as “I may not like what you do, so bloody well do what I prefer, and shut up“. Only this weekend, one young Conservative (who spent a couple of terms in a classroom before moving on the traditional route into non-classroom policy jobs in politically sympathetic organisations) “joked” that teachers using ‘child-centred’ measures should be “struck off“. This sort of increasingly confident attack on any form of difference or dissent is troubling in its own right, and I’ve covered the growth of the authoritarian movement in a previous blog. […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Ed Blog Reader.

LikeLike

[…] final cause is ideological. I’ve written about this before, too. Do not underestimate the degree to which education policy is being influenced by the same strains […]

LikeLike