I’m not sure whether this particular blog might lose me friends. It’s not intended to, but I’m going to stumble into an area where I know some people have very strong views. It was prompted by a post-parents’ evening trawl through some blogs, and I came across this blog by Dylan Wiliam :

I’m generally a fan of Dylan Wiliam, although I once tried to joke with him on Twitter, and I’m not sure my humour survived the transition to 140 characters. If I made any impression, it was almost certainly a bad one. Oh well. In any case, it’s not actually his blog on feedback which is at issue here – it’s a good piece, and I agree with the central message about marking/feedback. The bit I want to write about is this :

“Students must understand that they are not born with talent (or lack of it) and that their personalities do not determine whether or not they are “good at math” or “good at writing.” Rather, ability is incremental. The harder you work, the smarter you get. Once students begin to understand this “growth mindset” as Carol Dweck calls it, students are much more likely to embrace feedback from their teachers.”

The thing is, I disagree.

I don’t absolutely disagree: I am sure that there is some relationship between effort and outcomes. But I’ve seen a lot of people – good people who I have much in common with – write about the “growth mindset” in a way which is almost religious. Many take a similar line to that taken above, which seems to suggest that none of us are constrained in any way by ability, aptitude or whatever else you want to call any inherent attributes. The only thing that matters is effort, hard work, perseverance etc. Yet it seems to me that this is a theory which describes the world as we would want it to be, rather than the world as it is. This is a little personal too : my children are adopted, and while all have made incredible progress at school given the challenges they have faced, none of the three will ever be in any top sets, and two will continue to struggle throughout school. This is absolutely not down to a failure to try hard enough. I recognise that I am in a comparatively rare position of being an academic high-achiever with academically low-achieving children, and perhaps that perspective is one reason why I don’t see the “growth mindset”, as it is currently promoted in some quarters, as the inspirational positive principle which others do.

I’m going to structure this blog in a way which will hopefully be easy to follow. First, some evidence and anecdotes which seem to contradict the way Dweck’s theory is increasingly being presented (I entirely acknowledge, by the way, that Ms Dweck is much more nuanced in her conclusions than is sometimes suggested by those who cite her name while outlining a much more black-and-white worldview). Then I’ll note some arguments as to why we should be rather cautious about adopting the “Growth Mindset” approach as some sort of universal principle. David Didau has already covered much of this ground in his blog, but if we never allowed for repetition in the blogosphere, there’d be nothing left on the internet except rude videos and pictures of kittens, so I’m going to do it anyway.

I’m a long-winded old git, so I’m also providing a handy summary for those who don’t like reading much.

Summary

- The above quote is wrong, and so is the notion of “Talent = hard work + persistence”

- Dweck’s careful research is metamorphosing in the hands of others into a vacuous slogan

- Ability, or talent, is significantly constrained by factors external to the student

- These disadvantages cannot always be overcome

- An education system which refuses to recognise these disadvantages punishes children, teachers and schools unjustly

- The “Talent = hard work + persistence” version of the growth mindset is very useful for sociopaths

- “Growth Mindset” is potentially the next “learning styles” or “progress in each lesson” fad

- I have a bucket of penguin-regurgitated fish dinners waiting for any teacher who tells my children they only failed because they didn’t try hard enough, and for any head who uses the growth mindset to avoid providing the additional assistance they need

What’s it all about ?

Dweck’s broad theory is that students tend to fall into two camps : those who attribute their outcomes to external/ unchangeable factors such as intelligence or ability, and those who attribute their outcomes to internal, changeable factors, such as effort and perseverance. The latter group, she argues, then do rather better than the former when they come across challenges. This is not quite the same as the version of Dweck which is gaining traction rather quickly in the English education system, which is closer to the quote I took from Dylan Wiliam’s blog above : that the only determinant of outcomes is effort and perseverance. Dweck can’t be blamed for that, and I can see how her theory could, in the hands of those of us who don’t have to meticulously footnote our tweets and policy statements, gradually metamorphose into the idea expressed above and in many other places.

Case not proven

Others have noted that education evidence is often quite a long way from “evidence” as it might be understood in the scientific world. Often, evidence is the result of a single, unreplicated study. For example, Jack Marwood recently demolished the oft-repeated “evidence” about “good” and “bad” teachers . Frequently “evidence” and “personal anecdote” are unfortunately confused; for example grammar schools have never been vehicles for social mobility according to rather solid data, yet thousands continue to claim the opposite. Occasionally, the “evidence” is actually not evidence at all, but nonsense; for example, remember “learning styles”, anyone ?

Where does Dweck’s work fit in ? Well, I’m not even going to try to offer a critique of her study – that’s way above my academic pay grade. However, others have done so, and have not always supported her conclusions. As an example, I would steer readers to the following article, which is on the whole positive about Dweck’s theories: interview with Dweck . The point here is that there have been other studies which have not been able to replicate Dweck’s original results. In addition, Dweck herself noted that there was no apparent correlation between performance at school and whether one has a “growth” or “fixed” mindset.

I’m not saying her theory is wrong. I’m merely noting that there is room for reasonable disagreement here. The growth mindset theory is not a fact, like gravity or evolution. It’s a theory, which sounds nice, but is unproven as a universal principle applicable in all situations. So having established that there’s room to disagree without being burned at the stake as an unrepentant luddite of educational theory, let me go on to make some observations which contradict the idea of “growth mindset”.

Nature

When going through the adoption process, I did the sort of research and reading which you might normally associate with a PhD (it seemed to me reasonable that if one was about to take on the responsibility for children, one should put a bit of effort into preparing for it). I certainly read more about this than I ever did for my PPE finals at university. And what I found was something which even today I don’t like : there does appear to be a very significant body of evidence which suggests some element of intelligence is genetic. I’m not going to argue the ins and outs of that here. Feel free to google the “nature versus nurture” debate for yourself. However, the bottom line is that I very much did not want to believe that intelligence was in any way hereditary, but I was forced to concede that what I wanted to be the case, is not what is actually the case.

If a hefty amount of what we understand as intelligence is in fact something we either have or we haven’t, then at best, the “growth mindset” theory is going to be limited to trying to achieve better outcomes for individuals who have a lower potential range of outcomes than other individuals, and at worst, it’s meaningless.

Quite clearly it is not the case that, as Dylan Wiliam put it in his blog :

“Talent = hard work + persistence”

Generously, one might rephrase that as :

“Talent = Genes*(hard work + persistence)”

Nurture

Adoption and twin studies have largely informed the conclusion that significant amounts of ability are inherited, and thus nothing to do with effort or hard work. But we also need to look carefully at nurture too. Children born into higher socio-economic groups get a lot of advantages in terms of child development, many of which feed into ability at school : vocabulary, stimulation inside and outside the home, diet, parental encouragement, early reading and so on. Of course I am in no way suggesting that all middle-class households provide wonderful home environments and all working-class households do not. But the evidence on this is again, fairly clear.

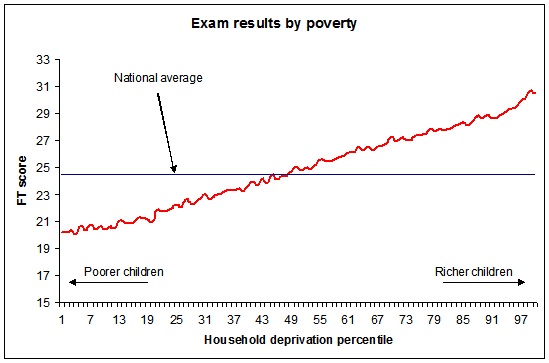

The graph below (by Chris Cook, and shamelessly lifted from Jack Marwood’s blog), is about as clear an indication of this as it is ever possible to show.

Indeed, there’s even the rather chilling possibility that such advantages of wealth can create further physiological advantages in some children, to add to the existing genetic advantages they may already carry. Susan Greenfield’s work on the development of intelligence in infants suggests that developing processing ability may be closely linked to the number of connections or neural pathways formed within our brains in our early years. These connections are multiplied by various stimuli which are not exclusive to middle-class households, but are perhaps more likely to occur within them (I’m paraphrasing – awfully – a presentation she gave to Ken Robinson’s National Committee for Creative and Cultural Education back in my civil service days). The good news is that the brain retains plasticity beyond infancy, so further connections can be developed. The bad news is that the same factors which make those connections more likely to occur in middle-class infancy, remain relevant as the child ages – further increasing their relative ability. This may well explain the often noted observation that wealthier children who start school with apparently lower ability than poorer children, accelerate past their less advantaged peers as time goes on.

To a certain extent, it doesn’t matter whether these advantages are nurture or nature or a combination of both. The inescapable conclusion is that there is a direct relationship between socio-economic status and outcomes. I don’t know any but the wilfully blind who deny this, by the way. Now this is where I start to really struggle with the “growth mindset” idea as it is often presented. Because if the growth mindset theory holds, then logically we would have to accept that the lower your socio-economic background, the more “fixed” your mindset, while the students with the “growth mindsets” all happen, coincidentally, to be from richer households. That seems unlikely given that we’re talking about an attitude of mind here.

This sounds a little like a counsel of despair, but one simply cannot reconcile the idea of the growth mindset, as presented repeatedly by well-meaning people, with the graph above. Our equation thus seems to have become :

Talent = (Genes + socio-economic background)*(hard work + persistence)

Anecdote

I often criticise people for the typical failure of mistaking a collection of anecdotes for evidence. I was going to write here about my own experience as a deeply lazy child who nevertheless achieved top grades in O-levels and A-levels, then went on to Oxford to obtain a good degree (yes, ok, a 2:1) despite spending 6 days of each week doing nothing but playing squash and rugby league, or lounging on the back quad while appreciating the apparent ubiquity of lycra cycling shorts, followed by one massive essay crisis from 8pm to 2am on a Sunday night. I was then going to contrast that with the experience of my beloved children, who work far, far harder than I ever did, both at home and at school, struggling to achieve in Year 6 that which I had already mastered before I even went to school. My own children not only have different genes, but they have some early life experiences which have quite clearly contributed directly to finding schoolwork a real struggle – no matter how hard they work. Fortunately, nearly all their teachers, and their school, have recognised these very real issues and have done their level best to provide assistance. Which is good, because if you think my blogs are occasionally angry, you should try telling me that you think my kids don’t work hard enough. But those are anecdotes.

Similarly, it would be anecdotal to note that I’ve now taught more than a thousand students by my estimation, and amongst those thousands, I would say with some certainty that the relationship between their effort and outcomes was, at best, limited. I have a party trick. It’s not a great party trick, because few parties last 7 years, but nevertheless: give me the KS2 data for previous achievement of a Year 7 student, then let me read their first piece of extended written work, and I can predict with remarkable accuracy which students will end up achieving A grades at A level in seven years time, and which students will not be able to stay in sixth form because they won’t get the necessary GCSE grades. And it won’t matter whether I teach them or not. And nor will the accuracy of those predictions be affected by whether they are students who work incredibly hard, or students to whom everything comes easy – as it did for me back in the Neolithic period. Still, it’s just anecdotal.

So let me just put it like this. Dear reader, think back to when you were at school. Or indeed, if you’re a teacher, think of your classes. Do you remember that student who always got excellent grades despite never breaking sweat ? Do you remember that lovely child who worked so incredibly hard but just never quite managed to achieve what her cruising classmate always did ? How can we reconcile those near-universal experiences with the idea of the growth mindset as “talent = hard work + persistence” ? We can’t. In every one of our schools, every day, carefree but able children are achieving better outcomes than Stakhanovite but less able children. That is not because the more able children have a more positive mindset – indeed as noted before, Dweck herself found no correlation between outcomes and mindset in schools – it’s because they are more able in terms of what the education system recognises and rewards as “talent”.

So you, a random anonymous blogger, are saying that the world-famous Carol Dweck is wrong ?

No. I’m not saying that at all. Dweck oversaw a study which produced certain results, from which she drew reasonable conclusions. Others have not been able to replicate those results. This is very common in the field of educational research, and does not mean she is wrong. I have absolutely no problem with the concept that there is a relationship between effort and outcomes. If I’d put more effort in at college, I’d have had a better chance of achieving a first. If my children put less effort in today, they’d have even less chance of achieving a Level 3 in maths by the end of Year 6. I’m yet to meet a teacher who doesn’t accept from their own empirical observations that effort can impact on outcomes. That is not my objection at all.

I merely think some growth mindset promoters are perhaps overegging this particular pudding. It simply isn’t the case that there is conclusive evidence that all we need to do to help all children achieve 100% is to convince them it’s all about hard work and not about ability. I fully accept Dweck’s argument that students with a growth mindset may be less disenchanted by failure, and perhaps even more adventurous or resilient. But that does not seem to me to be the same as accepting that children who hold a growth mindset outlook will necessarily outperform children who do not hold such views, and nor does it follow that those with a growth mindset will necessarily perform any better than they would if they themselves did not hold such views.

My objection is to the way in which Dweck’s conclusions are rapidly metamorphosing into something completely different, and thus reinforcing the set of existing bonkers principles which are largely shaping education policy. Dweck’s well-meaning and perfectly reasonable research may well end up producing toxic outcomes if we don’t nip it in the bud.

Bad for children

It’s interesting that people can look upon the same words and see completely different meanings. Some people will read the quote from Dylan Wiliam’s blog at the top, and his equation, and see that as an inspiring message for children of all abilities; the educational equivalent of Obama’s “Yes We Can”. Yet others, and I include myself here, look on those words and see something which can easily be interpreted by the intended beneficiaries as a form of blame.

To a certain extent, I feel the growth mindset is the equivalent of putting a penguin next to an eagle and inviting them to both take off. When the eagle is a speck in the sky, the observer then tells the penguin that the only reason it isn’t also flying is that it isn’t putting enough effort in. If only it flaps its wings harder, it’ll be chasing the eagle in no time. At which point, I hope the penguin regurgitates fish into the silly observer’s face. It’s not a lack of a positive attitude which prevents the penguin from flying, it’s a lack of wingspan !

So it is for some children. For all the reasons above, some children will be penguins in an education system which values flight as the ultimate goal. And when they flap their wings as hard as they can, repeatedly, and still fail to take off, they are then hit with a double whammy : firstly they’ve failed to fly, and secondly they’re being told that the only reason that they’ve failed is because they’re not trying hard enough. There may be some people reading this who are now hopping up and down saying “but that’s not true, that’s not what the growth mindset is about, it encompasses failure and attitudes to it!”. But most adults would fail to grasp that kind of subtlety, so why would we expect less able children to be able to perceive it ? The logic is fairly inexorable. If their school is pushing the “growth mindset” message in a slightly bastardized way which states that only effort and persistence determine talent or outcomes, then those children will very clearly understand that when they fail to achieve the best outcomes, their failure is their fault. Now if they haven’t put any effort in, they may take that one on the chin. But what if they have worked hard? What if they swallowed all that growth mindset guff about it all being about effort, and then still crashed and burned ? Still their fault ? That’s a pretty terrible message to send to a child. Especially when we know it’s not true, given the evidence of genetic and socio-economic contributions to talent and outcomes. We need to handle such theories with care and avoid damaging simplifications.

A penguin with a growth mindset

Bad for teachers

One of the aforementioned bonkers assumptions already at play in the education system is that the most important input which affects results for children is the teacher (or, in the case of defined groups of children, the school). These are assumptions which are absolutely central to performance related pay, the Ofsted inspection system, “closing the gap” policy and so on. The only problem, as Blackadder said to Baldrick, is that they’re bollocks. Others have written excellent blogs on how the impact of the teacher, or the school, is peripheral compared to the impact of external factors, not least those mentioned above regarding socio-economic background and genes, so there’s no need to repeat those arguments here.

The danger of the “growth mindset” as it is being promoted, is that it fits very neatly into this pantheon of bollocks. If one accepts the premise that any child, from any background, with any starting ability, can achieve 100% based solely on hard work, then we can merrily blame the teachers and schools for all outcomes, because if the least able child starting school does not “close the gap” with the most able child, then that must be because schools and teachers haven’t done enough to make the child work hard, or show sufficient “grit”. You can see some of this argument starting to emerge in the media now, as various commentators – often those who pronounce simplistic cobblers about how “good” teachers make X years of difference over “bad” teachers – start talking about the importance of schools teaching “grit”, or “moral character”, or “resilience”. None of these things are bad in themselves, but they are not being promoted as “it would be nice to have more of this”, they are being promoted as “and if your inner city kids don’t all turn out to be Stephen Hawking, then you have failed to give them the only tools they need – a protestant work ethic and a stiff upper lip”.

In other words, it feeds into that Godawful laminated-card slogan which one hears far too often at all levels of the education system: a “No Excuses Culture”. I have a friend who coined his own equivalent of Godwin’s Law, which is that anybody who uses the term “wealth-creator”, without irony or qualification, is an arse (he didn’t use the word arse, but my blog profanity only goes so far). I would suggest that anybody in education who uses the phrase “No Excuses Culture” without irony or qualification is also an arse. Because a “No Excuses Culture” which refuses to acknowledge such very real issues as the external constraints shaping a child’s life and abilities, is basically just a “No Reality Culture”, or perhaps a “No Intelligence Culture”.

I loathe this inaccurate, simplistic nonsense. But the “Growth Mindset” is already being adopted by the proponents of such nonsense as evidence that they were right, that everyone can indeed achieve the same outcomes, and that only the teachers’ and pupils’ own sweat and grit stand between them and a clean sweep of A* grades. Handily, this excuses Ofsted from having to exercise any actual judgement about schools which isn’t simply a comparison of absolute outcomes, and it excuses some lazy or unimaginative schools from having to offer any additional or creative support or help to the disadvantaged students – after all, they’re just not trying hard enough. Make them do more. After school sessions, weekend sessions, holiday sessions. Work harder and longer, get the results. That’s the growth mindset, right?

Bad for society

It’s long been noted that those who achieve great success in life tend to downplay the role of happenstance or external circumstances in helping them reach the top. Indeed, read any interview with a very rich person and you’ll often find them emphasising how with hard work and persistence they overcame great disadvantages which clearly seem very real to them, even if the burden of attending only a minor public school, and having one of the ten family businesses go through a sticky patch, doesn’t necessarily seem like a great disadvantage to the rest of us.

However, what the “Growth Mindset” does is feed very nicely into that self-delusion. It is astonishing how quickly “Talent = effort + persistence” becomes “I am successful, therefore I worked hard; you are not as successful, therefore you cannot have worked as hard”, which rapidly becomes “I deserve everything I have; you deserve nothing”. The consequences of that sort of mindset are extremely grave for society as a whole, from the erosion of support for the welfare state, through tax avoidance, to the increasing categorization of the poor into “deserving” and “undeserving”. Hands up if you haven’t already noticed the growth of those themes in our society.

Of course, some might argue that the “growth mindset” is actually helpful in this regard, by giving children the belief that they can overcome their disadvantages and escape their background. This is, in my humble opinion, self-serving rot. If we as a society refuse to acknowledge that ability is, in fact, shaped by hugely influential forces which exist beyond the control of the individual, then we abdicate any responsibility for seeking to address those disadvantages. Redistributive taxation system ? No, people can all rise by their own efforts. Welfare system ? No, people are poor because they don’t try hard enough. Sure Start early years intervention to try and tackle some issues early? No, they can close the gap at school through their own efforts and those of their teachers.

In terms of society, I see “Growth Mindset” described in the terms “Talent = effort + persistence” and I hear Ayn Rand’s siren call of unmitigated sociopathy. I don’t think it’s coincidental that the concept began and developed in the US, where the American Dream ideal is still clung to despite all the evidence that social mobility there is hardly less sclerotic than it is here.

Boris : “I got here by working hard. Show some grit, ragamuffins.”

Boris : “I got here by working hard. Show some grit, ragamuffins.”

So what would you do, you fatalist loser ?

Just to be clear again, I am not in any way denying that there is a link between effort and outcomes. Nor am I suggesting that we, as teachers, should tell children that it is not within their power to improve their outcomes. We absolutely should emphasise the importance of effort, and encourage them to see failure as a learning process rather than a discouraging brick wall. If these are the messages the “growth mindset” take into classrooms, then I’ll happily sing that tune. But, of course, I already do. Doesn’t everyone ?

There is no need for a binary position here. It’s not the case that you either have to believe that outcomes can be determined solely by effort and persistence, or you must imitate a 17th Century Puritan and preach predestination. It’s perfectly possible for us to adopt a position of encouraging effort as a means of improving outcomes, while simultaneously accepting the concept of external constraints and disadvantages which demand additional support, and will lead to lower outcomes than the less disadvantaged might expect. This will allow us to reach much more accurate and fair evaluations of teacher performance, and also avoid the danger of heaping blame on children for outcomes which they could not reasonably avoid.

In David Didau’s blog he noted that the questions I’ve raised above, and others have raised elsewhere, are valid ones, and he acknowledged that it would be worrying if growth mindset was being interpreted in that way in British schools. But he didn’t think it was. I think it is. The simplistic, inaccurate version of “growth mindset”, which could be written as “Talent = effort + persistence”, for example, is precisely the sort of message which is gaining traction amongst education policy shapers and enforcers in this country, not least because it fits beautifully with Ofsted’s existing simplistic inaccurate positions on school performance and closing the gap, and the DFE’s simplistic, inaccurate position on performance related pay. Now Dweck may never have intended that her theory be bastardized into nonsense, and then used in a damaging and oversimplistic way by such intellectual giants as Wilshaw and Gove, but nevertheless, in my opinion it is.

I have written in the past about the need for greater nuance in education policy. That also applies to the interpretation and application of educational research such as Dweck’s. The danger of an education system which is as centralised as ours now is, and in which schools have become so hypersensitive to an overbearing, untrustworthy and arbitrary behemoth like Ofsted, is that very quickly, carefully researched, nuanced ideas with some evidence behind them, rapidly change to become damaging centrally-dictated orthodoxies pretending to be universal panaceas.

At some point in the past, the not-irrational idea that it might be useful to try using different methods in lessons to get the message home, became the concept of “learning styles” which had to be shown in each lesson. In the last two years, the perfectly sensible idea that occasionally students might benefit from a little more in-depth consideration of their own work, has become a mountain of compulsory double-marking, endless DIRT and colour coded dots. The growth mindset is in danger of heading that way; I see too much wholehearted adoption of an oversimplified, and thus inaccurate, stance towards student achievement, based within the profession on a well-meaning desire to promote a positive, inspirational message of hope, but outside the profession supported by those advocating a self-serving philosophy which justifies inaction and victim-blaming.

PS – Penguins can’t fly. But they can swim much better than eagles. My kids swim really well.

[…] now Growth Mindset turns out to have been hokum after all. Once more, teacherly suspicion turned out to be […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] It you want to face some stringent critiques of Dweck’s mindset work, or at the very least, their application in schools, read David Didau‘s bluntly titled, but typically knowledgeable: ‘Is ‘Growth Mindset Bollocks?‘ and then read @Disidealist‘s powerful social critique ‘Telling Penguins to Flap Harder‘. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] the supposed evidence of student success. An early skeptic, Disappoined Idealist, hit a nerve with a brave little commentary, December 5, 2014, wondering whether the Growth Mindset described a world as we wanted it to be, […]

LikeLike

A direct challenge to Stanford’s Carol Dweck Mindsets theory.

As previously Ms Dweck refuses to engage.

https://wp.me/pateI-SX

LikeLike

Great reading!

LikeLike

I loved this article so much that I wrote about it in my Quora post!

https://www.quora.com/Does-hard-work-really-pay-off/answer/Chang-Liu-362?share=587fb6de&srid=hGTEO

These hucksters leverage social media, Ted talks, and real media to schill for book sales and paid corporate speaking engagements.

Self help is in and of itself an oxymoron.

LikeLike

[…] of overly simplified applications of concepts which actually require nuance and care. Kohn and other educators have critiqued the ways in which the blanket application of mindset theory and […]

LikeLike

[…] not a fan of “growth mindset” and earlier today Alfie Kohn shared a blog post by the Disappointed Idealist that makes my case. I urge you to read […]

LikeLike

This post is completely fantastic. Thank you for writing it. I also wonder whether the school environment is a factor here. From my experience: I had all the advantages of genes and class, and yet my small government school was poorly resourced and working within some pretty lousy paradigms and policies. And then there were the cultural norms I didn’t conform to, which lead to me being bullied from an early age. I was an intelligent kid who massively underperformed because the system offered no ways of learning that suited me, little respect, creative freedom, agency or autonomy for the students, and no psychological safety. All my ‘effort’ was going into just trying to survive, mentally and physically. I got rubbish marks, scraped into an Arts degree, and then found University was a different kind of learning environment. I ended up with a first and a PhD. Like you, I now have two kids whose experiences are vastly different to mine. One who’s autistic, one who’s dyslexic, and both of them have ADHD. The growth mindset is particularly hard in kids like them. At school, they’re penguins in the desert. My dyslexic son exhausts himself trying to learn in a world where the thing that is valued most – the key to all worth and success – is the thing his brain finds difficult to do. His brother learns easily, but is putting his ‘effort’ into coping with an overwhelming torrent of sensations emotions. So I guess one of my annoyances with the growth mindset is that it doesn’t acknowledge different kinds of effort, or school or home environments that generate the demand for that effort to be directed not into ‘learning’ but into ‘surviving’.

LikeLike

Hard *on* kids like them I meant! Also should say they are safe and happy in a small, caring play based school, but I am concerned here about what will happen in a more mainstream school

LikeLike

Hard *on* kids like them I meant! Also should say they are safe and happy in a small, caring play based school, but I am concerned here about what will happen in a more mainstream school

LikeLike

I was puzzled by this blog, because it ascribes to me views that I don’t think I have ever held. I have managed to trace the source of the phrase “Talent = hard work and persistence” to a blog that my publisher in the US posted in my name, and I while I agree with most of what is in the blog, I am going to request that the sub-head “Talent = hard work and persistence” be removed because I think it’s nonsense (as well as being a tautology).

For the record, let me say that I have written on numerous occasions about the influence of intelligence on academic achievement. For example, Ian Deary and his colleagues found that around 80% of the variation in GCSE grades in England are accounted for by IQ measured at the age of 11. Moreover, the genetic component of intelligence is large, and substantially inherited. I have been highly critical of authors like Ericsson who have claimed that elite performance is solely the result of deliberate practice and pointed out that differences in talent are real.

All this said, while the effects of growth mindset may have been hyped, are modest, and difficult to replicate, recent work by David Yeager and his colleagues have shown that growth mindset interventions of as little as one hour’s duration can have a substantial impact on student achievement. It’s not a magic bullet, but anyone serious about increasing student achievement needs to take Carol Dweck’s work seriously.

LikeLike

Fair enough. If the blog was ghost-written by someone without your knowledge, then I’d be having a stern word with your publisher.

LikeLike